Rebecca. Henry. I killed them. Those were their names. That they were chickens was much less important to me than that they had names. Especially since I didn’t know that they had had names before I killed them.

An Ag sciences guy I knew had grown weary of me complaining about how bad the food was during a summer job I had in high school, so he offered them to me. He, the seasoned hand, was supposed to do the dirty work, but he stalled and then bailed.

“I can’t do it,” he said, handing me the knife, standing down hill off in a patch of trees.

I felt it was important, if your plan was to eat “meat” that you participate in the process of making it meat. And so I did. It was the best chicken I had ever had. It was also Rebecca and Henry. It would always be Rebecca and Henry. Immutably unchanging.

In any case I didn’t kill again until I killed Malo. He, sadly, was a pitbull who played to type and attacked me for no reason, latching on to my hand and refusing to let go. I brandished a pocket knife at him in the hopes that he’d do what a human would do and manifest some sort of instinct of self-preservation.

He did not, and as I worked the knife toward his eye I realized that I couldn’t do it either. My left hand was hamburger now though as he jerked back and forth on it, but the eye was so…human.

Lieutenant Colonel David Grossman wrote a book on killing called On Killing. A book I sought out after killing.

But his body was not. He was stabbed (distancing language) until he let go. Then he was shot. I couldn’t take him to the vet with stab wounds. I couldn’t let him live around my two year old daughter, or my 110-pound wife. I dispatched of his body in a dumpster.

After this a desire to make sense of the entire process of how the life-no life works had me seeking out answers by hunting. Wild boar, mostly. Which accounts for how the next thing I killed was a goose. I couldn’t sneak up on a house cat much less a boar. I didn’t know what the hell I was thinking.

But the one goose I shot, I only wounded, and afterward, after the shooting, the goose sat up and looked at me as I approached it. The guys I was hunting with, hardcore cattle ranch, country cats, urged me to “break its neck.” I declined and walking back with my shotgun I explained to the goose that taking it to the vet at this point was also a nonstarter. But an apology was due. So I apologized. Then I shot it in the head.

And every bite of that goose that I took after that had me thinking about that goose, and well after I had eaten that goose, I think about that goose.

Lieutenant Colonel David Grossman wrote a book on killing called On Killing. A book I sought out after killing. His claim is largely that humans, like many other mammals, have an inborn and instinctive aversion to killing their own kind.

Bears, tigers, and rattlesnakes, he claims, when fighting each other rarely fight to the death. Our nearest animal relatives, primates, are fierce adversaries but they have fights that more often just maim, weakening a rival’s competitive advantage, without reducing the social grouping’s numbers.

Modern humans, however, as a result of conditioning, will murder each other against instinctive drives, Grossman says. This is causally connected, if I understand him correctly, to the amount of mental health issues we’ve had post-modern wars (pre-mass media battlefield data suggests most soldiers did not actually shoot to kill claims Grossman), and contributed largely to the wars at home later.

This has bothered me for years though.

You see, thinking about people who are most often in a position to end the lives of others, the soldiers Grossman himself is so familiar with, is something I’ve been doing a lot these days. With military men I know deploying themselves to Ukraine to fight Russians — not sent…just…going — I’ve begun to wonder how you go from doing whatever your job is to doing as you’re told and shooting at people who look like you.

“I remember the exact date and time I killed a man,” said a man who told me he had killed a man. The only other people I know with this kind of recall are lovers. And people who have won lotteries.

Which is to say while I understand giving the order to kill, managing to make sense of being the one who does the killing bedevils an easy understanding.

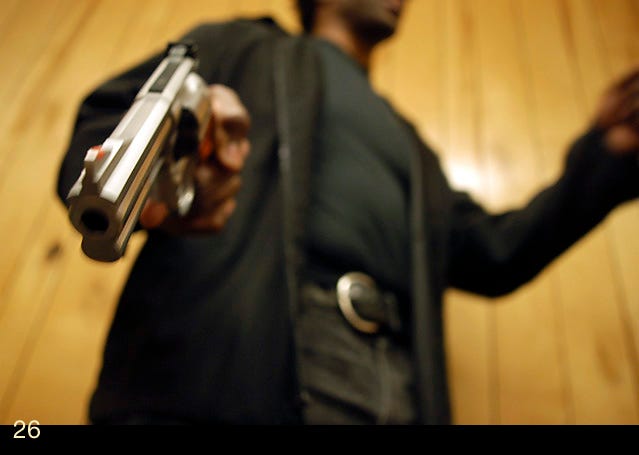

Moreover, if you’re reading this on a Sunday, and I’m writing this on a Saturday night, the numbers of Americans killed tonight for reasons much less significant than global realignment is so regular as to not even qualify as news. Yes, the usual suspects — video games, violent movies, a death culture, a drug culture, a gun culture — are toted out to explain, but the explanations don’t explain it all.

“I remember the exact date and time I killed a man,” said a man who told me he had killed a man. The only other people I know with this kind of recall are lovers. And people who have won lotteries.

But he killed a man defending someone who was about to be killed by that man. So, he felt remorse. But regret? Not much it seemed.

“I killed her because she and my business partner were going to run off together and steal my shit.” This guy’s business was drugs and the claim he made was that these were the rules of engagement. Rules that anyone in that business should understand. He seemed to, after it seemed to him that I did not require it, not have any remorse or regret.

“I worked Artillery,” he looked at me, while smiling, through thick glasses and talked about sneaking his way into the military during World War 2. His job was, according to him, an abstraction. They got calls of positions to fire on and they did. He said that he estimated that had killed “thousands.” These were, by 1943 rules of engagement, bad guys.

He had stopped smiling, and seemed haunted and regret and remorse were not even strong enough to cover what played on his face. But he was from the generation that didn’t talk about it much.

Which is where I started to think the key resided. Not in his silence, but in the tools used. In this instance? Artillery.

Right now Russia is pounding Ukrainian cities with Artillery. Even if history has shown that bombing — outside of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — is less effective in breaking the will of a population, it’s pretty effective in what War Colleges are expecting to happen next. That is: people entering cities to shoot people who look like them.

Amidst bombed out buildings, burned out cars, and near-cinematic hellscapes, it might be quite easy to have a hard time believing that you’re shooting at people who look like you. People who are (at this point fueled by righteous anger) also shooting at you first, maybe.

It’s the othering that makes it all possible though.

From Daryl Gates’ belief that Black people’s necks respond differently to choking to Harry S. Truman’s willingness to trust any man who wasn’t a “chinaman, nigger” or as later expressed (and often) a “kike,” it’s really the othering that makes it all possible.

So when morale problems beset the early stages of Russian soldiers rolling in to pre-bombed Ukraine it makes sense. Killing that guy over there, that guy just standing there, won’t really make sense no matter how many shoot-’em-up movies you’ve seen. If he looks like you.

But change the stage set — a Warsaw ghetto, a Chicago ghetto, a bombed out and depleted Kyiv — and it might get easier too.

“You know what G-d sees when He sees you?” He had been a military chaplain and he worked at a publishing house post-service. They published religious tracts. I worked for them for such a short time I’ve never even put it on my resume.

But I didn’t know, so he told me.

“He sees you as an infant.” He looked over his glasses. There was not even the slightest bit of con in his delivery. If the divide between cynical opportunism and true believerism still held he was much more the latter. “And He sees you that way always.”

This is a tragedy of tragic proportion though, this endless killing, killing, killing. And we do it to each other every minute of every hour of every day. We must do it because we love it because very little else explains it. So we keep killing, ceaselessly, and keep being killed. It is, to put a lie to Grossman, just our nature. Immutable. Unchanging.

Waiting for the uplifting kicker?

Yeah. Me too.

Wars are different, I was told, by my father-in-law. He was a forward observer in WWII, he did the calculations & called in the coordinates for the artillery. He never spoke much about the war until our son came along & asked questions... then it was like the floodgates opened. One of the most memorable things he told the boy (now a grown man) was that it was either shoot that guy rushing toward his foxhole, or get shot. Him or the German. No calculation was necessary at the time, not if he wanted to go home.

He would be horrified by what's happening today. He opposed the invasion of Iraq, although he thought Afghanistan was righteous. He opposed Libya, and passed before we got to Syria, Yemen, and the like. He frequently told our son, though, that he fought in Europe to show the world that it couldn't keep happening. He died not liking Germans very much, and detesting the Japanese. He would be appalled that the world has allowed this nightmare to continue. If they survive as a country, will Ukraine have a new "greatest generation?"

Most of all, what I REALLY wonder, is why people don't see the parallels between what's happening in Ukraine and what has happened in Iraq, Yemen, and Syria. You & I both know why it is... boils down to pure racism, doesn't it? I think that's the part that frustrates me most of all about all this 'rah rah Ukraine' (FYI I am supporting the Ukrainians as much as I have supported the Syrians) stuff. If the Yemenis, Syrians, and Iraqis had been white & blond & blue-eyed, would we have handled it differently? If the people dying most often at the hands of cops were fair-skinned & blond, would there be a rush to reform? I fear I already know the answers.

Sheesh. But…appropriate for the times.